Best advice to maintain strength without a gym?

Steve Jeffries, Senior Physiotherapist and Strength and Conditioning Expert shares the best advice to maintain your strength training if you can’t get to the gym. If you are not sure why you should be worried about your strength… how about half the injuries and more performance! The World Health Organisation also recommends two resistance training sessions per week! Read here for more info and learn more about our Steve, Merv and our expert team here.

I can’t get to the gym, what happens?

As COVID fears subside, many of us are travelling again after for many, solid blocks of training or strength work for rehabilitation, injury prevention and performance. What happens to your strength if you can’t get to the gym for a while?

- How long are strength levels maintained once training stops?

- How quickly does strength decay happen?

- And the most important question, what can be done to stop strength decay?

What happens when you stop training?

Based on a review of 27 studies about the development, retention and decay rates of strength in rugby and American football, whose subjects were completing between 2 and 4 strength sessions per muscle region, per week. The research suggest that strength levels are maintained for up to 3 weeks following ceasing training. That’s pretty good! Probably longer than you expected right? Unfortunately decay rates increase after that.

How quickly does strength decay?

Let’s look at a study on elite cyclists who completed a 25-week block of strength work twice a week alongside their usual training, then stopped for 8 weeks. At the end of the strength block their max strength, max and average power output on the bike all increased significantly over the group who were doing usual training. At the end of the 8 weeks without strength training the gains they made had all but disappeared. Twenty-five weeks’ worth of work, gone in 8.

So how much do you have to do to maintain strength levels?

Based on a study of 70 people where participants did 3 sessions per week of strength training for 16 weeks then were divided into 3 groups. Group 1 reduced training to one session a week (30%) Group 2 to one set of the exercise once a week (11%) and Group 3 ceased completely. In groups 1 and 2 strength gains were maintained, in-fact the younger participants (between 25-35) continued to gain strength. This was sustainable for up to 8 months. The take home message here is that doing anything helps, the key is maintaining intensity. They still lifted heavy.

Steve Jeffries is an expert in rehabilitation and performance.

What does it all mean?

If we combine the information from the above studies, you don’t lose strength as quick as many think, so don’t get too stressed out! After 3 weeks things start to disappear rapidly, but you only have to do a small amount to maintain, as long as you can achieve a high intensity! This means, without the luxury of being able to stack plates on a bar and lift heavy we need to be creative. Using angles, leverage and whatever heavy stuff you can find can still provide sufficient stimulus to maintain strength.

You probably shouldn’t expect to get any stronger until you get back in the gym if you were training regularly before-hand, unless you can get your hands on some really heavy stuff, but if you are new to the strength training world or were thinking about giving it a go, it’s a great time to learn some movements that can be directly transferred to the gym! Why not get your muscles used to resistance training and hit the ground running when you get back to the gym!

Don’t go it alone!

Like any other exercise, strength training is a skill. If you’re new to it, get help from someone who knows what they are doing. If you have experience, but need some ideas of how to achieve a high enough intensity for your home program, the team at Star Physio are here to help. Click here or call 64249578 to book with Steve or one of our other experts.

References:

Rønnestad, B. R., Hansen, J., Hollan, I., Spencer, M., & Ellefsen, S. (2016). Impairment of performance variables after in-season strength-training cessation in elite cyclists. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 11(6), 727-735.

Bickel, C. S., Cross, J. M., & Bamman, M. M. (2011). Exercise dosing to retain resistance training adaptations in young and older adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(7), 1177-1187.

McMaster, D. T., Gill, N., Cronin, J., & McGuigan, M. (2013). The development, retention and decay rates of strength and power in elite rugby union, rugby league and American football. Sports Medicine, 43(5), 367-384.

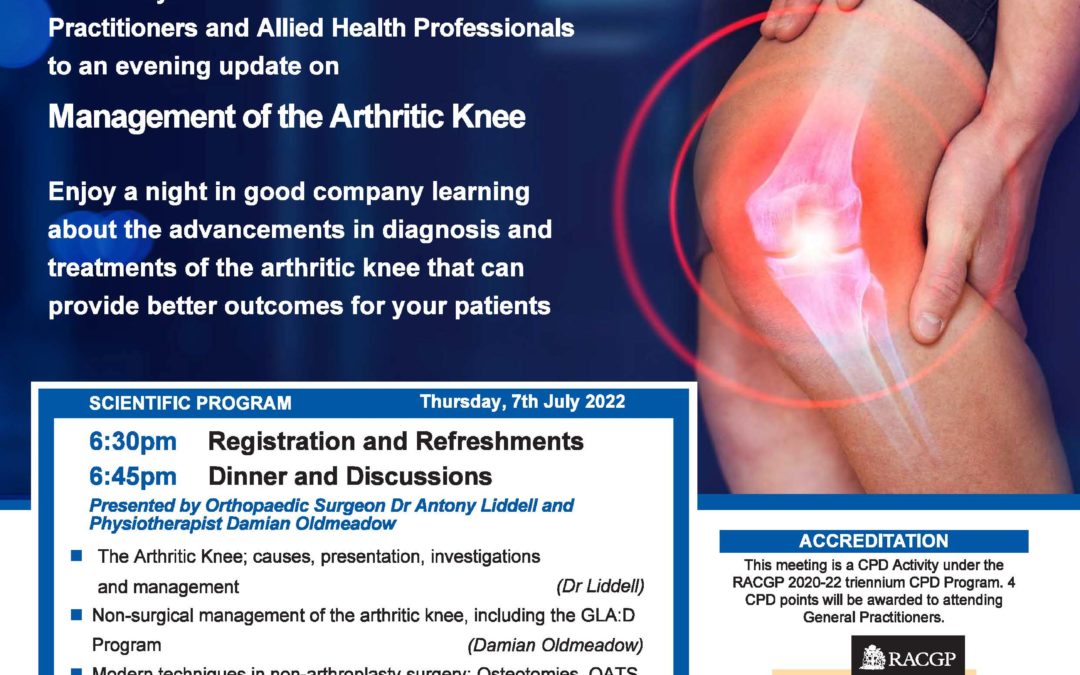

Knee rehab to recon in 2022

Knee rehab to recon in 2022 Are you a GP dealing with patients with knee pain? Are you up to date with the latest research and information on conservative management of knee pain, arthritis and the GLA:D Program? Are you aware of the new advances in technology and...

Triathlon Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy for elite triathletes. Triathlon Australia Team Physio Blog #1 James Lewin. Star Physio Senior Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist Earlier this year, I was asked to be team physiotherapist for the Triathlon Australia ‘Podium Centre’ team, who are coached by...

Hamstring Injury

Hamstring injury treatment. Australian rules football is the most prevalent and physical sport in Australia, well known for the athleticism of the players to manoeuvre and kick an oval-shaped ball in various directions. For many years in AFL, hamstring strain has...

Jai Hindley Wins Giro!

Jai Hindley wins Pink! Perth's Jai Hindley's historic Giro D'Italia victory, and the winner's "Maglia Rosa" or Pink Jersey, is a long journey with many people involved over many years. Having a father who was a former high level racer and continuing cycling tragic was...